My Common Journey

I’ve known my autistic son was special for two decades now. Through those years, I’ve also come to know many families with special needs children, and I’ve noticed so many commonalities in our experiences. It’s like we’re all walking different paths through the same forest, encountering the same landmarks, just at different times and in slightly different ways.

Wherever you are on your journey right now, you’ll probably recognize these milestones I’m about to share. If you’re just at the beginning, my hope is that this prepares you for what lies ahead. Maybe it will help you avoid some pitfalls I stumbled into along the way. I wish someone had given me a map when I started this journey.

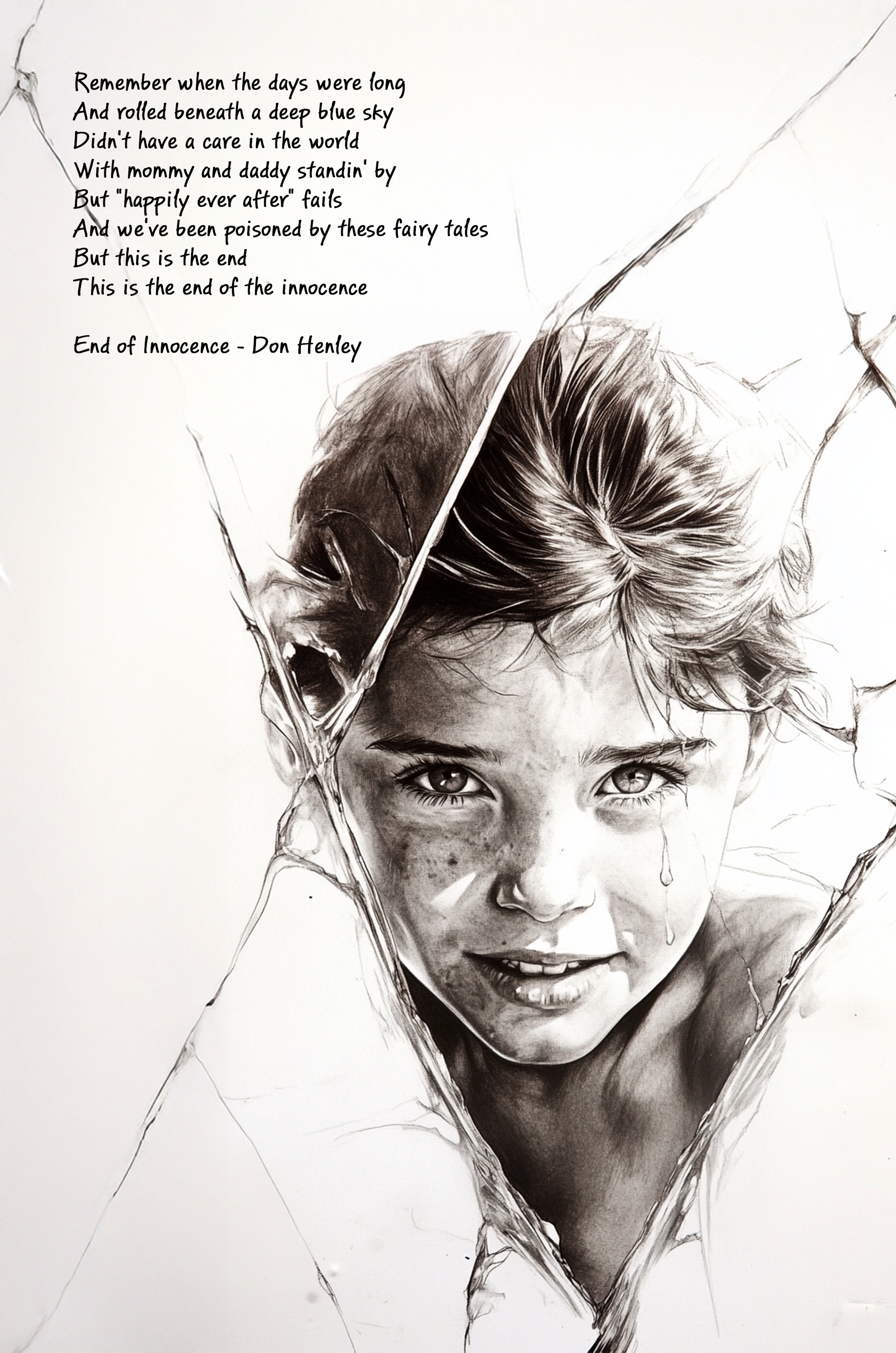

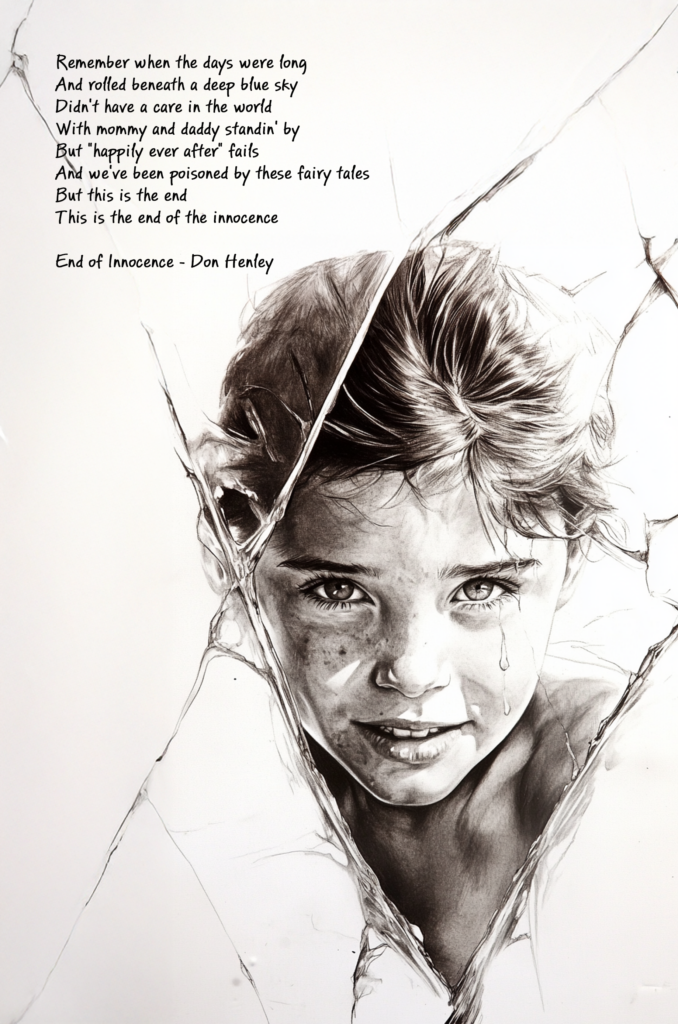

Vicarious Dreams

Children are natural fountains of hope. They bubble with possibilities, don’t they? When my wife became pregnant with my son, I was absolutely ecstatic. We were in our early thirties, financially established, had been married for over a year, and the timing felt perfect for us to have a child.

I was overflowing with hope for our bright future—full of love and wonderful family experiences. Like all new parents, we didn’t truly know what we were getting into, but we believed we were ready for anything. And we wanted all the things parents normally dream of: the joy of raising a child, being there for the ups and downs, eventually becoming grandparents, and nurturing that relationship for a lifetime.

In short, we wanted everything parents normally get when they have a family.

My child was supposed to be perfect. In my mind, he would have all my strengths without being burdened by any of my foibles or weaknesses. He was going to be naturally strong, athletic, and coordinated. He would be brilliant, naturally adept at learning all subjects. I imagined him as extroverted but introspective—the master of all social situations, exemplifying virtue.

He would never make any of the mistakes I did. He wasn’t going to be merely typical—he would be extraordinary. In my mind, he was the manifestation of all that was good, a special gift to the world. He would have perfect motivations and barely require parental guidance. His stellar career would bring fame and notoriety, allowing me to feel enriched by my association with his greatness. My perfect child would help me become a better person through his flawless example of humanity.

But the truth is, not every child fulfills the dreams of their parents. In fact, no child does. Most typical children fail their parents in predictable ways, and most parents fail their children in ways that their children eventually overcome.

With special needs, though, these failures feel catastrophic. The dreams aren’t merely adjusted—they’re the first illusions to be completely shattered. And acceptance is the phoenix that must somehow rise from those ashes.

The Warning Signs

Looking back, there were signs that something wasn’t quite right. By six months, my son showed few warm, joyful expressions and made limited eye contact. By nine months, there was little back-and-forth sharing of sounds or facial expressions. At twelve months, he had little babbling, no gestures like pointing or waving, and rarely responded to his name.

By eighteen months, he had very few words, carried objects around for extended periods, displayed unusual hand movements, played with toys in unusual ways, and wouldn’t look when we tried to direct his attention. By twenty-four months, he still had very few meaningful phrases.

But the thing is, most people don’t immediately jump to the conclusion that their child has autism. The possibility feels too grim to entertain. Denial feels safer, more comfortable than thinking the worst. And it’s true—not every child with signs of autism has autism (Please, don’t grasp at faint hope because I said that.) Plus, autism affects every child differently. The deficits can appear random, with some developmental areas severely impacted and others not affected at all.

Being a new parent is incredibly stressful already. A baby is a huge responsibility, and there’s so much to learn about their care. Worries about their development only add to that stress. So denial is natural—even appropriate—until the warning signs become too obvious and too numerous to ignore.

For us, no single warning was enough. It was the cumulative weight of many signs that finally painted the undeniable picture.

The realization didn’t come out of nowhere. My son didn’t turn over in the womb. As a baby, he wouldn’t roll over on his stomach. He avoided eye contact and wouldn’t respond to his name. He made few vocalizations. He would stand on his tiptoes and flap his hands. My wife always thought his scalp smelled unusual. He didn’t play with toys appropriately, didn’t point, and wouldn’t look at what we pointed to. He didn’t learn by copying others.

The Sickening Realization

I remember the exact moment I realized my son had autism. My wife was visibly upset when she showed me a magazine article that listed signs of autism. As I read through it, I could easily recall specific examples of my son exhibiting each sign on the list. Before I even finished reading, I knew deep in my heart that my son had autism.

My denial—my willful ignorance of the truth—vanished instantly. Perhaps if the signs had been more ambiguous, or if I were more stubborn, I might have clung to denial longer. But I knew immediately, and I didn’t doubt it or fight it. My memory fades at that point, except that I remember I began to cry.

I spent weeks in tears, sobbing deeply for the loss of my illusions. My world crashed around me. My first thoughts, of course, were about how everything impacted me. All my dreams for the future seemed destroyed. Rather than celebrating my son’s achievements, I imagined I would spend my life making up for his deficiencies. I would be tied to a good school system, unable to move for career promotions. We wouldn’t be able to travel and enjoy life. It felt like everything was going to be awful from that day forward.

Then my thoughts turned to my wife, and my troubles doubled. She would need to provide lifelong care for our son. Her burden would never end. She would endure unending stress and worry about him and his future.

But when my thoughts turned to my helpless son, the pain was so overwhelming I couldn’t face it. My mind would go blank, and I would struggle to function. I lapsed into despair.

Our formal diagnosis came nine months after we already knew, and it turned out to be a non-event. We already knew what the doctor would tell us. We weren’t in suspense or shopping for a different diagnosis like some people who go from doctor to doctor until one tells them what they want to hear.

The Doctor of Dispair

The most memorable part of the consultation was an unpleasant interaction with the doctor. As it turns out, doctors can be difficult too. After waiting nine months for an appointment with the best specialist we could find, the doctor chastised us, asking, “What were you waiting for?” to bring our son in for evaluation. She said his signs were so obvious that we should have come in sooner.

This hurt in two ways. First, we had tried to get in immediately, but her staff had put us on a long waiting list. We didn’t bring him in sooner because we couldn’t. But she implied we weren’t good parents because we didn’t seek her diagnosis earlier. Second, she used this heartless approach to break the news that our child was moderate to severe with little hope of a neurotypical life.

Before my wife could explain through her tears that we couldn’t get an earlier appointment, I was so incensed that I was stunned into silence. I wanted to tell the doctor she was being terribly insensitive and should stick to research, but I wisely said nothing. The piercing look of hatred in my eyes probably expressed my feelings clearly enough.

The doctor undoubtedly thought our reaction was to our own guilt over waiting, but it was actually in response to her false accusation that we had failed to properly care for our son. Mixed with those emotions was the stinging realization that our child’s condition was obvious and undeniable. We could see that too, but we didn’t need to hear it put so bluntly from someone who was supposed to be compassionate and helpful.

It would have been easier to accept such a bleak prognosis if the doctor had conveyed it more sensitively. I had to focus my mind on feeling compassion for the doctor. My mind wanted to dwell on how insensitive she was, but I reminded myself that she probably thought she was saying the right things to get my son the best care. This doctor was likely accustomed to parents avoiding the diagnosis to sustain denial, but we weren’t avoiding it—we simply couldn’t get in any sooner.

Further, I tried to remember that anyone who says unkind things to vulnerable people probably isn’t very happy themselves, so I should feel sadness and compassion for her situation. It took a lot of mental discipline not to keep replaying the hurtful interaction in my mind. My wife didn’t manage this—she spent years afterward harboring resentment toward that doctor. It was not a pleasant experience for either of us.

The diagnosis itself didn’t change much. The services we received didn’t require a medical diagnosis. It provided a few additional treatment options, but little in the way of substantive help. We completed follow-up testing—brain scans and the like—but obtaining a formal diagnosis wasn’t the game-changer.

Autism Radar

For anyone wondering whether their child is autistic, there’s an easier way to find out that doesn’t require a doctor’s examination: seek out a parent with an autistic child. We’ve lived with autism, and we know the signs. A parent who has lived with autism develops an intuition born from years of experience and constant immersion. Most of us can spot another autistic child almost immediately.

We concluded my son had autism when he was 18 months old. Once we noticed, the signs became clearer, sharper, and even more obvious. What always stood out the most to me was how separate our worlds were. He refused all eye contact. Looking into someone’s eyes is the most basic of interactions—it’s acknowledging that someone exists. I spent hours trying different things to engage him, to get him to look at me, even for just a moment. But he literally would not look into my eyes for an instant.

And it wasn’t just that he refused to look at me—he refused to acknowledge my existence altogether. Not in the teenage way of making a scene about ignoring someone, but by acting as if I wasn’t even there. If I tried talking to him, he would ignore me or walk away. If I tried touching him, he would ignore my touch. If I offered him something, he might take it, but without any acknowledgment, as if some object had just appeared for his amusement with no cause. I was just another object in his world, and not a very interesting one at that. And this went on for over a year.

By the time he was three, he would interact with me occasionally, responding to me now and then. But he still had no speech. In fact, he didn’t speak until he was six. We had experts tell us if he didn’t speak by age five, he never would—they were wrong. He had no interest in speech except to obtain something he wanted, and grunting worked well enough for that. He had no interest in hugs or affection. My wife and I were useful servants, but little more to him at that stage.

The Suffering of Special Needs

Nobody wants to believe their child has special needs. Special needs persons often live a hard life full of suffering. Their cognitive disabilities put them at a significant disadvantage. They have limited abilities to communicate their needs and get them met. And what’s worse, is that they face negative judgments for their incapacity, even from their own parents.

Ignorance isn’t bliss—it’s pain. Ignorance is not knowing what you need or how to get it. It’s a life of not getting your needs or wants fulfilled. Special needs people have limited resources to help them. For better or worse, our capitalist system denies basic resources to people to motivate them to work, but special needs people often have limited skills and aren’t that productive in conventional terms. Thus, they fall to the bottom and live in poverty.

Capitalism without compassion would simply allow special needs people to fall through the cracks. Even higher functioning individuals who can hold down jobs often make minimum wage with no benefits. Special needs people are more likely to fall victim to predatory lenders. Most live at or below the poverty line. Unless they have caring people devoted to them, they don’t enjoy a high quality of life.

My son is blessed with a devoted and loving family. I hope your child enjoys the same advantage. But what about special needs orphans? A society can be judged by how it treats its most helpless members. For a highly developed country, our provision for special needs persons is lacking. Some states have reasonable social services, but even in the best states, they are underfunded and overwhelmed. Some private charities provide assistance, but this is like trying to extinguish a forest fire with a garden hose—better than nothing, but not by much.

The Challenge of Social Rules

Complicated sets of rules are hard for them to follow. Special needs persons are often rule followers, but they don’t have the depth of wisdom from what they’ve learned. Many don’t have high emotional intelligence to understand their own motivations. They often lack the empathy to understand the golden rule. They learn from the results of their behaviors, but those results depend on what was reinforced and what was punished.

Following simple, clear rules is how they function in a group. They’re prone to inadvertently violate social norms because they simply don’t grasp the subtle and unwritten rules of interpersonal relationships. Many don’t read body language or understand facial expressions unless specifically taught. Some don’t understand right and wrong intuitively, and they can unknowingly break laws out of ignorance.

My son doesn’t have typical emotional reactions. In circumstances where most people feel sadness, like death or loss, he laughs. It’s as if his brain is miswired to trigger laughter instead of tears. He can’t contain his laughter at funerals. We had to work with him for months to get him to stop laughing at the sound of babies crying.

Thankfully, he isn’t motivated to cause pain. If he were sadistic and thought pain and crying were genuinely sources of entertainment, we would have a more serious problem. But this doesn’t appear to be the case. He’s not motivated to make people cry just to laugh at their tears. I suspect when he feels sadness, he’s experiencing the same emotions the rest of us do, but the outward expression is laughter rather than tears. But even if that’s true, it doesn’t make it any easier to explain at a funeral.

Elaborate or complicated philosophies are beyond many special needs individuals’ comprehension. They can’t be taught ethical systems with vague language, nuance, and contradictions requiring analysis and wisdom. Special needs persons aren’t trying to live as stoic philosophers or experience “oneness” with others—they’re learning and applying basic rules: Don’t hit, pinch, squeeze, or bite people. Ask for what you need and want. If you don’t get what you need and want, don’t hit, pinch, squeeze, or bite your caregivers.

Beyond that, the rules may get more complicated depending on their capacity, but they must remain simple and basic to be understood and followed.

Learning Virtue Through Repetition

But special needs persons can learn basic virtues. With repeated attention and modeling, they can learn to emulate virtue. If virtues are modeled for them and reinforced, they can become wonderful people.

My son has learned generosity—he will offer his food and other enjoyments to others. I’m always pleasantly surprised when he offers me something I know he would rather keep for himself. He has also learned loving kindness—actions toward others motivated by warm feelings. He knows when he’s being kind and acting out of love for his family, and he gets very excited about it. He asks for praise about being a good boy, and we heap praise on him to nurture this seed.

I’ve explained to my son many times that the most important thing he can learn to enjoy his life is to be kind to his caregivers. It’s like “don’t bite the hand that feeds you.” Realistically, caregivers will do whatever their duty requires or whatever they’re paid to do. However, if they receive kindness in return, they’re more motivated to ensure proper care and go above and beyond for their charge.

Compassion is much more difficult for many special needs persons because they often lack the basic understanding of self and other—the foundation for all empathy. The sense of self that Buddhists strive to overcome is actually needed to feel empathy. If you don’t have a sense of self, you can’t appreciate that others also have their own experiences. My son has developed compassion for his immediate family, but it’s still rudimentary. I know it’s there because he takes satisfaction in giving, expressing love, and being kind.

Special needs persons can live an exceptional life if they obtain the help they need. Like everyone else, they are products of their environment. They are often not burdened by the needs and wants that plague the rest of us. Special needs persons are worthy of love and acceptance, and they will return that love once you learn to enter their world. If they are in an environment that supports them and teaches them virtue, that’s what they enjoy internally, and that’s what gets expressed when they’re out in the world.

My Son’s Nana Was His Savior

My wife’s mother was very close to my son. She lived on another continent, so when she came to visit, she would stay for months at a time. Her visits were always welcomed—she didn’t interfere with our parenting or cause strife in our household. And she was enthusiastically and energetically devoted to our son.

If not for his Nana’s frequent long visits, I wonder if my son would have ever desired human contact at all. During that period when he would ignore me and my wife, he would interact with his Nana. I occasionally felt jealousy arise, but it was immediately replaced by gratitude for the good I saw coming from his budding relationship with her.

She would sing to him, read him books, and interact with him all day, every day, whether he seemed to want to or not. She was never dissuaded by him ignoring her, never put off by his lack of social skills, never angry at him or critical of what he did. She was always loving, accepting, and devoted to his care. If I make her sound like a saint, it’s because she was, at least to my son.

She was the first person he ever felt drawn to, the first person he wanted to interact with. She made him laugh—something my wife and I could never do. She helped him find a sense of humor and a playfulness he still has today. Whenever I see my son laugh, or particularly when he gets that devilish grin, I see his Nana coming through.

I have many beautiful pictures of the two of them together. The affection between them was deep and genuine. She passed away when my son was 16, but he still speaks of her often, knows she’s waiting to see him in Heaven-house (Have you watched Disney’s Coco?)

Despair and Your Special Needs Child

Children are a natural fountain of hope. Every parent has high hopes for their child’s future. Even devoted pessimists harbor secret hopes for a better future for their children. Parents often forge dreams of their child’s future greatness, hoping to live vicariously through them. When you realize your child has special needs, these dreams and hopes are dashed. Many parents lose all hope for their child. The absence of hope is despair.

A special needs child provides ample opportunities to wallow in despair. Spending time focusing on their deficiencies will inevitably lead you there. Since there’s nothing you can do to change their fundamental condition, any time spent in despair is utterly wasted. Despair drains your energy and motivation and provides nothing in return.

When I realized my son had autism, I saw no possible good that could come from it. I lost hope for myself, my family, and my son. I accepted despair as my fate, and it eventually became a sickening, low-grade depression. Combating despair requires rigorous mental discipline. Many people don’t want to engage in any kind of discipline, particularly a difficult mental and emotional one. Those people often remain trapped in despair, occasionally escaping into denial to relieve the anguish.

The mind easily and naturally repeats false negative narratives. It’s as if the mind creates a loop of negative thoughts and plays it endlessly, over and over. These negative thoughts get burned into your mind and heart, unintentionally, and to your terrible detriment.

My false negative narratives included some really harmful ones: Autism was nothing but bad in every way, and no possible good could ever come from it. My life, my wife’s life, and my son’s life would be a terrible struggle forever. There was no hope of our lives improving since his autism was permanent. It was pointless to consider other ways of looking at the situation because I already “knew” the awful truth.

These thoughts morph into a quick and nearly silent refrain, like background music. You don’t consciously realize you’re thinking these thoughts unless you pay attention to them. They fade into your subconscious mind, like a distant conversation you’re trying not to hear. Sometimes, these thoughts get emotionally triggered and are called to the attention of your conscious mind. This directs your attention and energizes these thoughts emotionally. You feel a dose of negative energy and a release of neurochemicals that brings you down, triggering other related negative thoughts and putting you on a train of thought leading straight to pain and suffering.

The Loop of Endless Suffering

Whenever this sequence starts, it must be redirected immediately. Noticing the pattern and choosing to cut it off by redirection is a mental discipline. If you don’t engage in this practice, you’ll follow that train of thought over and over again. Each time, it leads to misery. The more often you do it, the worse the problem gets. Your mood is certain to sour, and you can become depressed or remain locked in depression.

You need a list of counterbalancing thoughts you can rely on to change the narrative. To successfully redirect, you need a series of positive items to think about instead. When I’ve asked people to come up with such a list, most stare at me with a blank expression. Their minds have been so trained by negativity that they can’t conceive of anything even remotely positive. I was stuck in that place too, and it took significant effort to change it.

It isn’t necessary or helpful to dwell on negative thoughts, particularly if there is nothing you can do about them. It’s about applying the wisdom of the serenity prayer. Whenever negative thoughts arise, it should serve as a signal to redirect your thinking toward something else. Your goal is to shorten to zero the time between when you realize you’re starting a stream of negative thoughts and when you apply the redirect.

I have certain facts about my son that I refuse to dwell on because they merely trigger negative feelings I can’t do anything about: His intellectual development is that of an 8-year-old. He can’t safely cross a street on his own. He will always need 24/7 care and supervision. He will never have a wife and family. He has no friends and probably never will. As his immediate family dies off, he will live out his life alone. He will never experience many things most people take for granted.

Even making this list was painful, and I could feel myself staring down the abyss of despair. These are facts, and I acknowledge them, but it would be pointless and counterproductive to dwell on them. If you have a similar list and find yourself dwelling on these facts, you will become trapped in despair. It’s imperative that you learn to stop thinking about these things and direct your thinking elsewhere.

I have a “go-to” list for whenever some incident or thought triggers negative feelings about my son’s circumstances. I’ve trained myself to remember what I’m thankful for, even without being triggered by some negative thought or event.

I remind myself constantly of these things: He loves me openly. He is my friend and constant companion. He talks to me. He doesn’t defy me. I have the privilege of spending the rest of my life with him. He genuinely enjoys my company. He appreciates the activities we share. His smile brings joy to my heart. He is in good health. He can walk. He can perform most routine grooming and self-care tasks. He gives my life and spiritual practice depth and meaning. I owe all my spiritual growth to him.

When I redirect my thoughts to this list, I find myself not only avoiding despair but actually feeling genuine gratitude for the gift my son has been in my life. It takes practice, but this mental redirection has been life-changing for me. Your list will be different, but if you make your list and refer to it often always, It could change your life, too.