Grieving the Loss of What You Never Had

The day I finally accepted my son’s diagnosis, I sat and wept. Not just a few quiet tears, but deep, body-shaking sobs that seemed to come from somewhere ancient inside me. I wasn’t just crying for my son—I was mourning the death of a dream.

When you realize you have a special needs child, you will grieve. There’s simply no way around it. You had a vision of who your child would be, what your family would look like, the life you would share together. Then suddenly, that vision shattered. You lost the dream of your perfect, typical child, and instead, you obtained something you didn’t want or expect. Emotionally processing and accepting these truths is grief, and there is no avoiding the experience.

I don’t say this to discourage you, but to normalize what you’re feeling. The sooner you recognize that grief is a natural and necessary process, the sooner you can begin to move through it with purpose rather than simply being dragged along by it. How you process your grief will determine what you do about your circumstances. If you lash out in anger and retreat into denial, both you and your child will suffer. Your need to grieve doesn’t remove your child’s special needs. While you grieve, you will still need to devote yourself to meeting your child’s needs. This might sound overwhelming—how can you possibly tend to a special needs child when you can barely function yourself? But here’s the truth I discovered: helping your child is not a distraction or a burden. It’s the path to your recovery.

With help and awareness, you can shorten this process. You can avoid sinking into depression. You can find meaning and joy on the other side. And in the process, you’ll better serve your child who needs you now more than ever.

We all process grief differently. While the process can be described in general terms, each person finds their own path. I’m trying in this book to guide you to a quicker and less painful journey by pointing out the pitfalls along the way. That doesn’t mean the way I describe is the only way or the best way for everyone. By far the most common and most harmful thing you can do with your spouse is to judge and criticize them for how they handle grief. I’ve seen this destroy marriages that were otherwise strong. Your partner isn’t grieving “wrong”—they’re just grieving differently than you are.

Supporting Each Other Through Loss

To meltdown or not to meltdown, that is the question. When it comes to grieving as a couple, there are a few paths I’ve observed. If both spouses become overwhelmed with grief, it needs to be brief for the family to still function. If this leads to a catharsis and quick recovery, it may actually be the better method, as each spouse can process a great deal of grief quickly by “crying it out.” But if it leads to a prolonged period of deep mourning, it can lead to depression, which helps nobody. And if both parents are in full meltdown mode and withdrawing from the world, who is taking care of their special needs child?

If neither spouse melts down, they can both process their grief while doing what’s necessary for their family. This circumstance is certainly easier on the parents and the child, but if one or both are in denial, it isn’t leading to acceptance. My wife and I were fortunate in that we both processed our grief this way. We both were very sad and cried often, but we didn’t succumb to feelings of overwhelm or withdraw from the world, and we mutually supported each other. Neither of us became depressed, though the sadness took many months to pass. And critically, neither of us looked down in righteous judgment at the way the other handled our situation.

If one spouse melts down and the other doesn’t, both are prone to judge each other negatively. When one spouse feels the news is too much to bear and completely breaks down, they often do so with the full expectation that the other spouse should feel exactly the same way. The more emotionally distraught spouse might claim the other is in denial, unfeeling, and should be just as upset as they are. The less distraught spouse might claim the other is a “weak snowflake” that needs to “get over it” and get on with life.

As each spouse hardens in their respective positions, animosity builds between them. This is one of the prime contributors to the high divorce rate among special needs parents. If you find yourselves in this situation, please remember that different grieving styles don’t indicate different levels of love for your child. They simply reflect different emotional processing systems.

The Power of Non-Judgment

The traditional interpretation of grief stages suggests a linear progression from one stage to the next. But this doesn’t explain why these stages occur, doesn’t reflect the recursive nature of grief, doesn’t provide a conceptual reasoning for why the process unfolds as it does, and doesn’t mention that bargaining is a form of denial. The reality is much more complex and chaotic.

Your mind judges every thought and experience as pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. The natural reaction is to pull toward pleasant things, push away unpleasant things, or ignore neutral things. All thoughts and experiences carry emotional content. Mostly these are not strong or intense and are barely noticeable. But sometimes, these thoughts and experiences are powerful enough to overwhelm us. The emotional reaction to judgment can be lessened with intentional practice. We can learn to reduce the certainty of our judgments to reduce their impact. We can learn to reduce the importance we place on our judgments. Reducing the certainty and importance of judgments lessens the highs and lows that disturb our peace of mind.

But here’s the tricky part: your mind doesn’t just think these thoughts once. It puts thoughts and experiences on loops and plays them back over and over again. If an experience is emotionally powerful, your mind doesn’t want to forget it. These loops are constantly playing in your subconscious. The cumulative effect of all these emotional feedback loops is your mood, and these tend to be dominated by negative experiences.

When you have a strongly emotional experience—like learning your child has special needs—your mind creates a loop and plays it back over and over again. It amplifies the effect. It determines your moods and state of mind for long periods. When the experience is negative, it can lead to depression if not processed properly. The mind tends to focus more on negative feelings and experiences—it’s a survival instinct to avoid danger, hunger, and pain. It requires mental discipline and training to focus on positive feelings, especially in the midst of grief.

Our mental judgments create negative feelings, which is why non-judgment is a profound spiritual practice. There are three events that carry negative feelings: failing to obtain something you wanted, getting something you didn’t want, and losing something you had. These events are very common and occur thousands of times a day in varying degrees. The negative feeling they generate is automatic, and it creates sadness. The depth of sadness is directly related to the degree of desire and attachment. The stronger your attachment to the idea of a typical child, the deeper your sadness will be when facing a different reality. The natural reaction to negative feelings is to push them away with anger. A secondary reaction is to avoid them, ignore them, or deny the feelings exist altogether.

Learning to Accept What Is

Acceptance is the emotional clearing of the negative feelings generated by the loss of attachment. Anger and denial are easy and natural, but unfortunately, they’re also harmful and counterproductive in the long run. Embracing sadness must be chosen—the reaction is not automatic. Embracing what feels negative is not instinctual or intuitive. It often requires training through spiritual practice and cultivating the belief that sadness is the path to wholeness and healing. It’s a decision to drop all resistance to what is.

Embracing and enduring sadness is how people accept whatever happens in life. It’s not easy, but it’s the only path that leads to true peace. Grief is the processing of anger, denial, and sadness. Acceptance isn’t just learning to live with your situation despite your pain. True acceptance is a return of joy and happiness—not in spite of what happened, but because of what happened. Acceptance is the state of mind where you are no longer disturbed by the three emotions of anger, denial, and sadness. You’ve processed them fully and moved beyond them.

Life need not be a series of disappointments that accumulate into depression, but this is exactly what happens when people don’t grieve properly. Many people live in a state of low-grade depression, constantly fighting off sadness through anger, resistance, denial, and bargaining. But suppression doesn’t succeed—it only prolongs the pain.

Grief and Forrest Gump

If you have a special needs child, the movie Forrest Gump will likely stir deep emotions in you. The film artfully and poignantly illustrates both the difficulties and possibilities of a life with special needs. There’s a scene after Jenny leaves Forrest where he is overcome with grief and starts to run.

He runs across the country and keeps running. He runs for years and gains a cult following. He isn’t fully aware of why he’s running—he just feels compelled to run. He has no agenda, no political statement, no desire to influence others.

As viewers, we have the context of the movie, and we know he’s running from his grief over losing Jenny from his life. What nobody knows, even Forrest himself, is how much grief he has to process and how long he will need to keep running.

At some point, he’s run through his sadness, and he simply stops running and announces he wants to go home. Such is the way of processing grief.

Nobody knows how much sadness they must digest. Nobody knows how long it takes. When it’s over, your mind just stops thinking about it, and it’s over.

This running sequence is a perfect analogy for processing grief. Sometimes you just have to keep moving forward until one day, without warning, you realize the heaviest part of your burden has lifted.

The Swimming Analogy

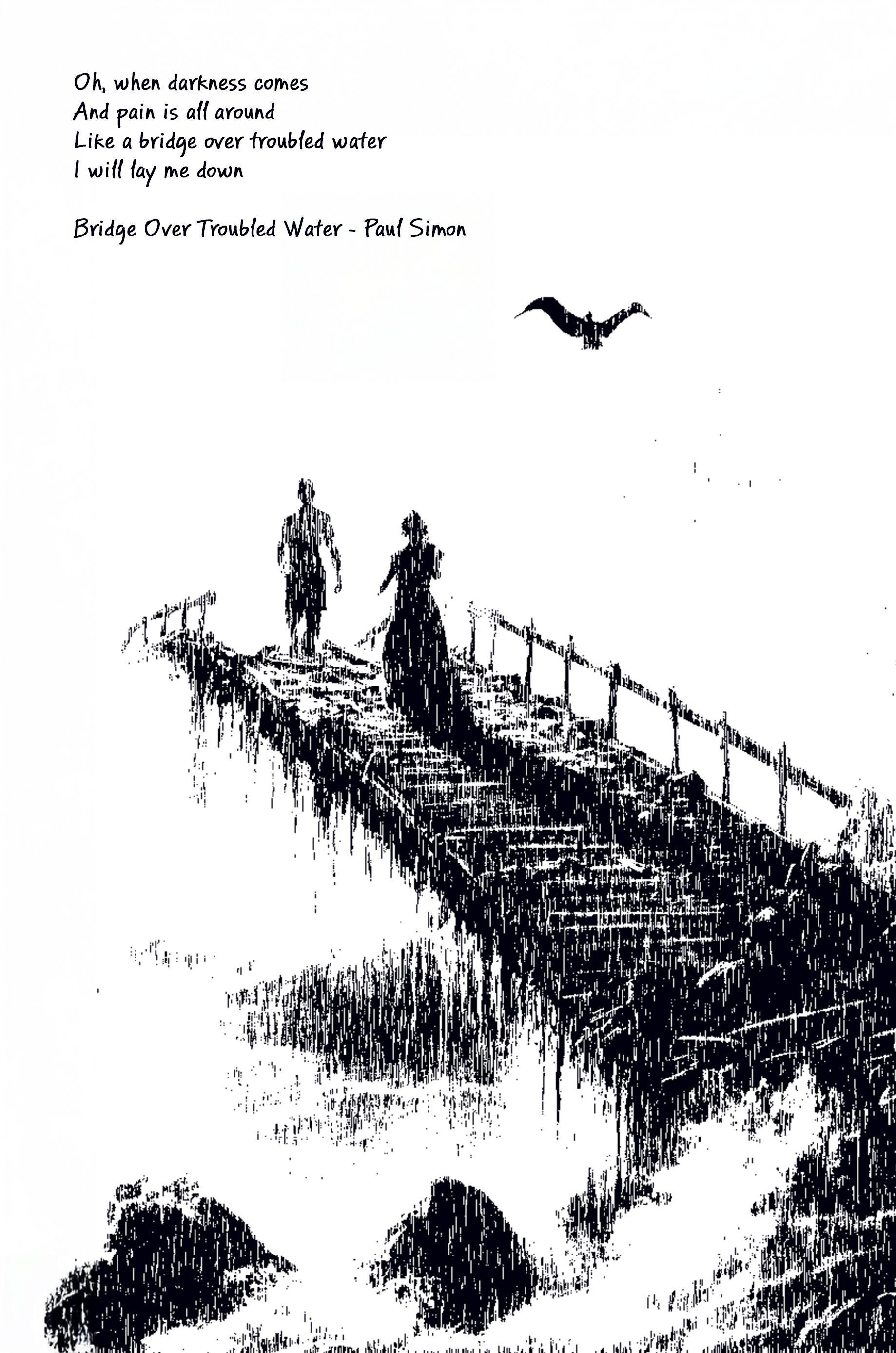

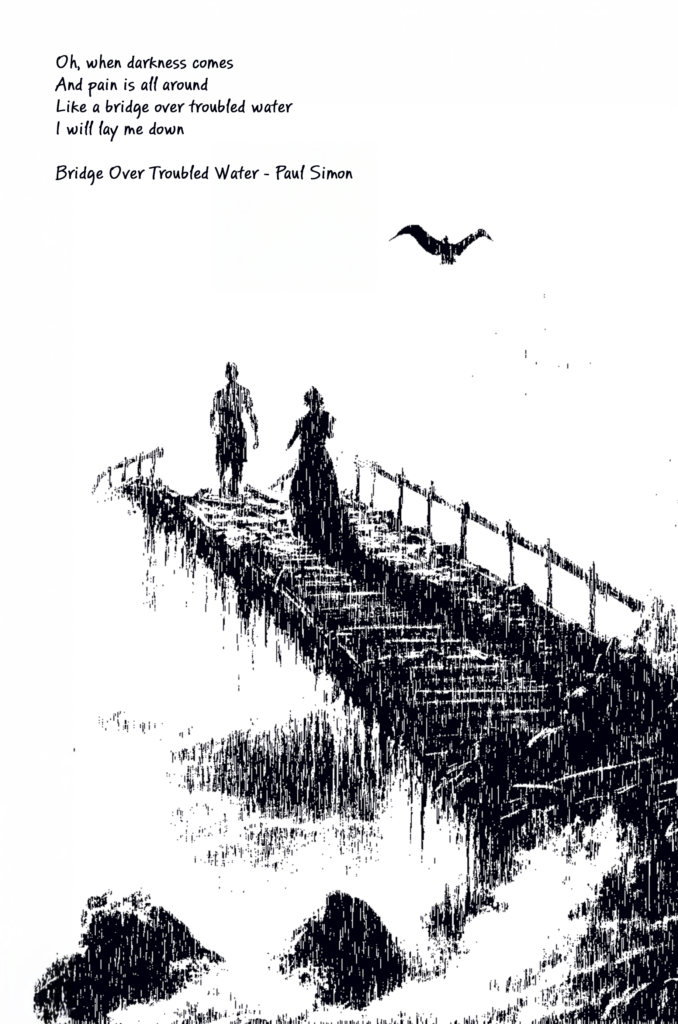

I like to think of the journey to acceptance as embarking on a long-distance swim in troubled water. Water is symbolic of emotions—it can be turbulent and difficult to swim in. Drowning in these emotions leads to depression. The length of the journey depends on how much sadness you need to endure to reach acceptance.

When you start, you often can’t see the distant shore. You feel like you’re entering an abyss or an endless ocean. But there is an opposite shore of complete acceptance, even if you can’t see it yet. It often takes faith to start the journey.

Denial and bargaining are like islands of respite along the journey. If you don’t stop at an island to rest occasionally, you risk drowning in depression. But if you stay too long on an island or mistake it for the shore of acceptance, you’ll never reach solid ground.

The journey to the shore of acceptance is a grueling swim through an ocean of sadness with brief respites on islands of denial. It’s exhausting. It’s frightening. Sometimes it feels endless. But I promise you—the shore is there. And when you reach it, you’ll find not just dry land, but a new perspective that will transform how you see your child, your life, and yourself. I know because I’ve made that swim. I’ve reached that shore. And though the journey nearly broke me at times, what I found on the other side was worth every difficult stroke.