How Charlatains Steal from Parents of Special Needs Children

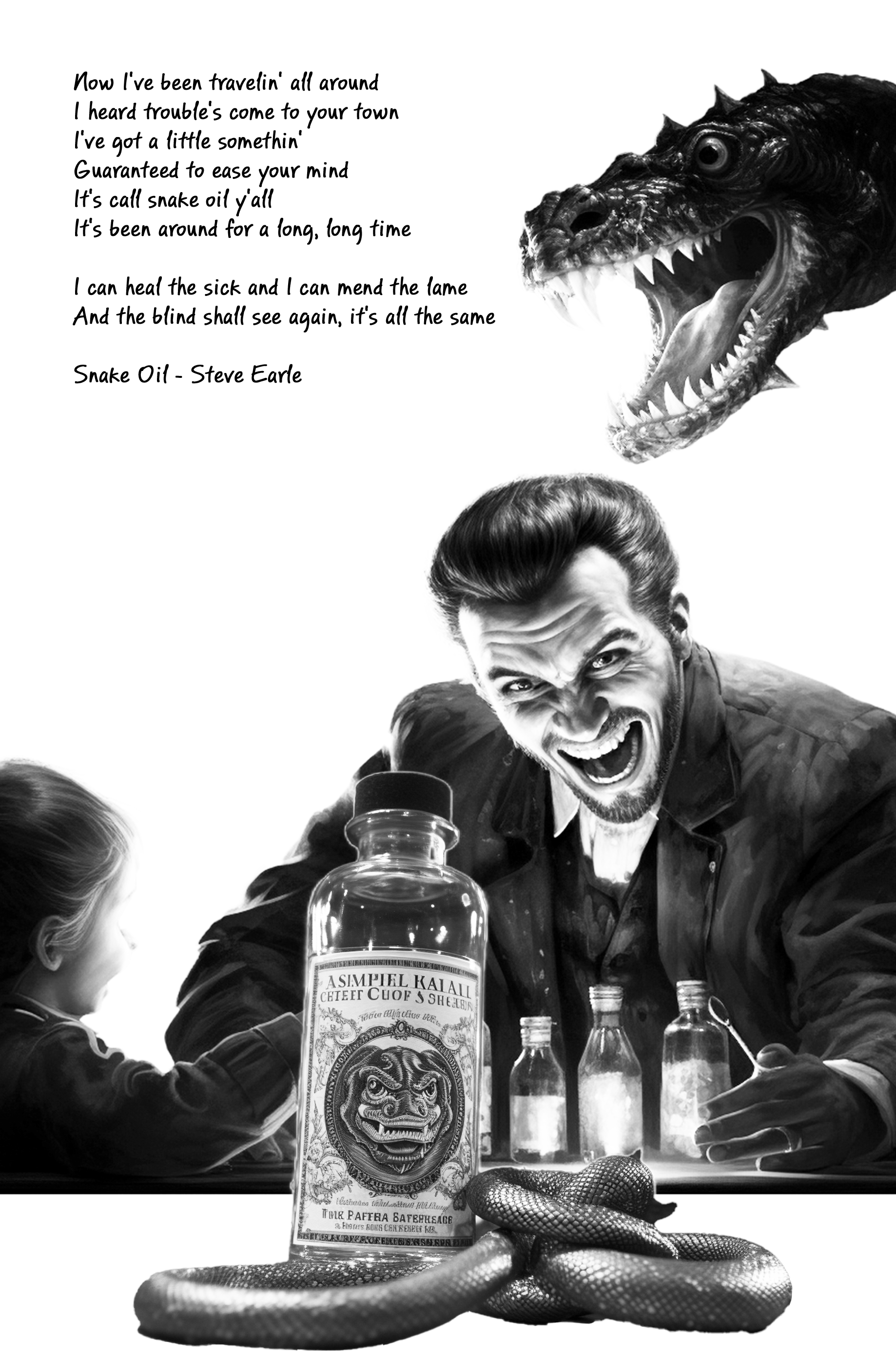

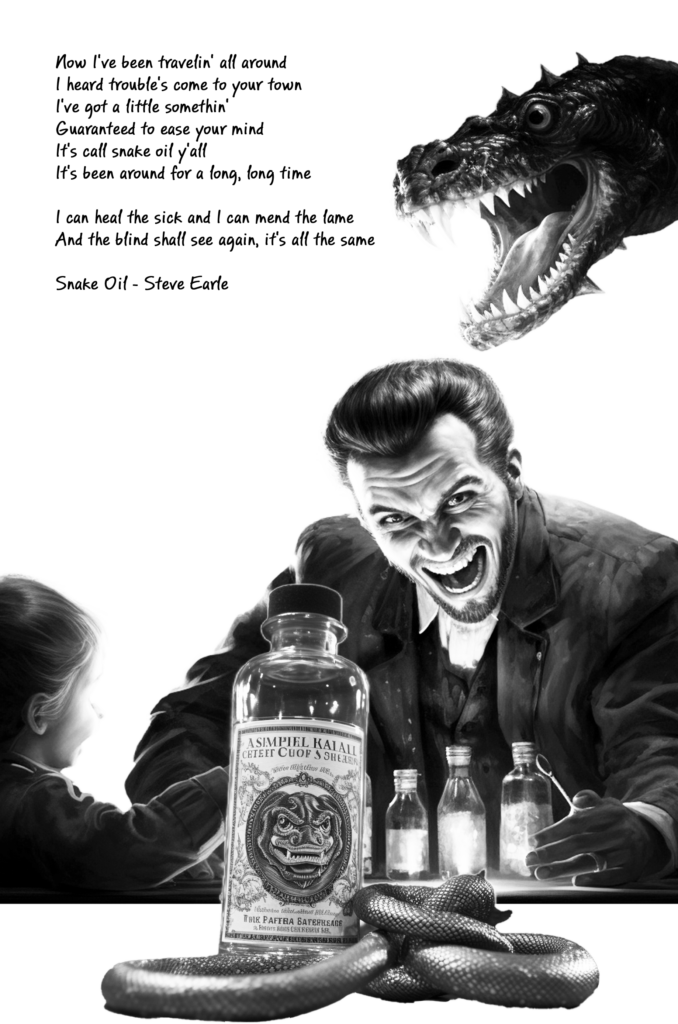

When I first set out to find possible treatments for my son, I felt like I’d stumbled into a carnival midway. There were so many options—ranging from the somewhat helpful to the plausibly effective, and then spiraling all the way down to the completely looney. I remember sitting at my kitchen table late at night, scrolling through websites, joining parent forums, and desperately trying to separate fact from fiction.

What struck me was that with the exception of ABA therapy, none of these treatments had any proven track record of effectiveness. Not one. Yet there I was, reading testimonial after testimonial from parents who swore that this supplement or that therapy had “cured” their child.

The internet is a wilderness of misinformation, much of it terribly plausible, teeming with snake oil products designed to drain your bank account while feeding your desperate hope. I found myself drawn to the ones that sounded most convincing—the websites with scientific-looking graphs, testimonials from “experts,” and promises of breakthrough results. These often turned out to be the least effective treatments, and in some cases, like mineral chelation therapy, demonstrably dangerous.

Delving into this issue gave me a deep appreciation for how badly we humans fare when doing our own research. Most of us—myself included—will believe almost anything if we want to believe it badly enough. It seems like we think truth can somehow be generated by desire alone or the repetition of nonsense. I’ve seen this same pattern play out in religion, politics, and especially in experimental medical treatments. We readily accept nonsense as fact if it confirms a belief we’re already clinging to.

Very few of us truly understand scientific methods or what separates a valid study from misinformation or meaningless anecdotes. Most snake oil pitches tout their “scientific validity” while offering zero actual studies or evidence beyond dubious testimonials. I was shocked by how easily I found myself nodding along with unsubstantiated claims from people I didn’t know, claims that were often completely fraudulent.

People who are desperate for a cure—parents like you and me—will try anything and pay anything if we believe there’s even the smallest chance for improvement. This desperation is the root of all snake oil scams. Our need for a cure provides the pre-existing bias that makes us want to believe nonsense because sometimes, a nonsensical hope feels better than no hope at all.

The most difficult problem with resisting snake oil isn’t skepticism—it’s the nagging fear and guilt that you might miss an actual cure. I worried constantly that if I didn’t try every treatment out there, I might miss the one thing that could have made all the difference for my son.

This fear of missing out is powerful. We have a friend who purchased her own hyperbaric oxygen chamber, spending tens of thousands of dollars on what most experts consider ineffective for autism. People only spend that kind of money because they’re terrified of regret—of looking back and wondering “what if we had tried?” That’s why snake oil salespeople continue to fleece innocent families out of huge sums every day.

The Lure of Medications

Let me be clear about something important: there is no medical treatment that effectively counteracts the mental characteristics of autism. None. And yet our culture is deeply biased toward pharmaceutical solutions for almost any health problem.

Most of us believe that if we have an ailment, all we need is the right pill to eliminate or control it. There’s a widespread belief that medicines can cure almost anything, including conditions like autism, which actually can’t be “cured” with medicine. Given this bias toward pharmaceutical fixes, it shouldn’t be surprising that nearly every special needs child I’ve encountered is on some combination of medications.

Experimenting with different medications until you find the “right one” is a fool’s errand with autism. I know a family with a son who has schizophrenia. The father told me the key to living with schizophrenia is finding the right medication. Not being an expert in that condition, I take his word for it. Pharmaceutical interventions absolutely have their place—but that place is not in treating the core features of autism.

I know one family that has taken their child to doctors hundreds of times over the years. They go with complaints about some ailment until they find a doctor who identifies something—anything—and offers them a prescription. Then they feel relieved that they’ve found the “right” treatment, and add this new drug to the list of medications their child is already taking. Then they go through this same process to find drugs for the side effects too.

Taking more than five drugs at a time is called polypharmacy, and it’s considered medically dangerous. At any given time, this child may be on a dozen or more medications—all considered necessary and backed up by many doctor’s appointments and tests. The parents consider each one medically necessary, and the list only grows longer. If any condition stops showing symptoms, they attribute that to the drugs and feel the need to continue them to prevent recurrence, ensuring lifelong medication.

Now, I’m not saying medications are never appropriate. Some autistic behaviors do require medical intervention. But the treatment isn’t for autism itself—it’s for a specific behavioral problem related to autism. I know one family whose autistic son is extremely compulsive and an “eloper” (meaning he tends to run away). Without medications, this young man is a genuine danger to himself and others. In those circumstances, medications that help with impulse control are necessary and appropriate.

Some children have a high risk of seizures, which is another circumstance where medication may be absolutely necessary. Where the health risk necessitates a medication, parents will and should do what’s right for their child. However, determining what’s medically necessary versus what’s medically convenient is open to different interpretations.

In my experience, most autistic children don’t need medications of any kind. Some parents—and I say this with empathy, not judgment—like the simplicity of sedating their child. When the child is drugged out, their behavior is more easily manageable, or they require no management at all. This might be convenient for the parents, but it does nothing for the child. I don’t believe this is a justifiable circumstance for providing drugs to children on an ongoing basis.

My son has never been on any medication other than antibiotics or other prescriptions for temporary conditions. We’ve been fortunate that he doesn’t have any condition that would require ongoing medication. He will probably never be on a regularly prescribed medication, and we’ve even written these instructions into his trust.

All drugs have side effects—that’s just reality. The families I’ve known who place their children on regular medications are usually managing some kind of drug cocktail with numerous pills. One pill for the primary condition, and the others for the side effects of the first pill. This is the typical path to polypharmacy and lifelong drug dependence.

A close friend of mine from high school is a pharmacist, and so is his wife (they met in pharmacy school). They don’t take any drugs other than the occasional ibuprofen. In fact, none of the pharmacists I know take medications regularly. The reason most offer is that they believe most medications are too powerful, and they would rather their body regulate itself, which it will if not constantly dosed with some medication.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

My journey with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is how I came to fully understand snake oil. A friend of my wife worked for a prominent doctor who specialized in this treatment. The first time we went to his office, we bumped into a famous retired astronaut who was seeking treatment for depression. I immediately felt a shot of validation—if an astronaut was here, surely this must be legitimate, right?

We felt this doctor (who wasn’t actually a physician) had credibility due to his years of supposed research in the field. We were offered a free treatment since my wife’s friend worked with him. He ran his tests and showed us these impressive-looking images of activity in my son’s brain, pointing out areas of “abnormal function” with authoritative confidence.

He interpreted these images and gave us the impression this treatment would work wonders for our son. He asked us to get up with our son and spend 30 minutes each morning looking at the rising sun before our next test a week later. Even then, I should have recognized the red flag—since this “sun therapy” was a new treatment element, there would be no way of knowing if any perceived improvement came from the magnets or from additional attention and morning sunshine.

We went back for a second test. He showed us more brain images, enthusiastically touting the differences between the first and second scans. He asked if my son had improved since the first treatment. I told him that my son seemed a bit happier and calmer, and he nodded knowingly, saying that was “a good sign.” We were then escorted into another room where we received the sales pitch options for ongoing treatment.

During that pitch, I felt all the emotional tugs that fuel snake oil sales. Perhaps this treatment really would work? My son did seem different. And most powerfully—would I really want to pass on what might be the treatment that could change his life?

When I got home, I started thinking more critically about how the sales pitch worked, and I did some additional research. What struck me as odd at first was how the entire experience resembled a timeshare or used car pitch. We were shown the product by a supposed expert, escorted to a different room to discuss the “package options,” and there was a clear expectation that we would sign up right there.

When I thought about the doctor’s interpretation of my son’s brain scans, it occurred to me that the colorful images could mean anything, or nothing at all. I wasn’t offered the scans to take for a second opinion. I was completely relying on this one person’s expertise and interpretations of colors on a computer screen. He could have told me the moon was made of cheese, and I wouldn’t have had any way to verify or disprove it.

As I researched further, I found others offering this service, and most of the websites made fantastical claims. Some touted their “exclusive treatment on the cutting edge of scientific inquiry”—a big red flag completely contrary to how science actually works. Real scientific breakthroughs don’t happen in isolation; they’re verified through replication and peer review. I read criticisms from legitimate scientists who confirmed what I was beginning to suspect—it was harmless but ineffective snake oil.

In the end, I decided to forgo the treatment that would have cost more than my car. Not because it was expensive, but because it was snake oil.

Brainwave Entrainment in His Crib

I have a confession to make. Before I was married, I put a lot of time and effort into studying meditation, sleep patterns, dream interpretation, and brainwave entrainment. I even developed custom brainwave entrainment mixes with different frequencies matching various brainwave patterns based on a typical 2-hour sleep cycle. I would record my dreams by keeping a tape recorder by my bed, and I would spend time analyzing them in the morning.

It was fun and interesting—it stimulated lots of memorable dreams, and it did improve my sleep. But it didn’t lead to enlightenment or liberation or any significant spiritual growth or emotional changes, so I eventually lost interest.

However, I did remember how it worked, and I knew it was effective at changing moods and stimulating brain activity. Most importantly, it was totally harmless. I reasoned that if autism was caused by scrambled and uncoordinated brain activity, perhaps synchronizing those patterns with brainwave entrainment might lead to some kind of breakthrough.

It’s exactly the kind of plausible-sounding pseudoscience that permeates websites peddling snake oil cures for autism. But since it was harmless, I thought I would give it a try. I set up my son’s crib with speakers on each side to create the stereo speaker environment needed for the brainwave entrainment effect without headphones. When he would nap, I would play my old brainwave entrainment mixes or just play alpha wave entrainment music.

My son responded the same way I did—he slept better on occasion and he awoke more rested. But there were also times when he clearly didn’t want to experience that brainwave state. He would resist it, and on those days he was actually less restful. It did absolutely nothing to rewire his brain or alleviate the symptoms of his autism.

Everyone holds out hope that their half-baked idea will be the next Lorenzo’s Oil—the miracle cure discovered by persistent parents that the medical establishment missed. It was worth a try. I knew it would do no harm. But like all snake oil treatments, it did not work.

We dabbled in music therapy for a while too. Mostly we ended up listening to a lot of classical music, which I enjoyed probably more than my son did. For a couple of years, he became absolutely obsessed with Coldplay—he would listen to the same songs on repeat for hours. He still enjoys music, and he is still autistic. The music didn’t “cure” anything, but it brought him joy, and that counts for something.

Eating Therapy

Autistic children often develop strong aversions to loud noises, certain textures, or any variety of sensations. It’s quite common for them to develop aversions to certain foods, which can lead to extreme limitations on diet. My son self-limited his food to KFC chicken nuggets and cantaloupe. That’s it—he literally only ate those two foods, and he would go without eating rather than consume anything else.

While we were considering our options, one of the students in my son’s class had a feeding tube that protruded from his skin near his stomach. The tube had a cap that could be opened so that liquid nourishment could be injected directly into his stomach. We observed with this child just how far autistic children would go in their self-limiting behavior. The idea that “if they get hungry enough, they’ll eat anything” simply isn’t correct for many autistic children. When my son was down to only two foods, we felt we needed to act.

We sent him to a feeding specialist. It sounds doctorly and medical, but it wasn’t—she was just a therapist who was willing to force autistic children to eat. She would make them keep food in their mouths and not spit it out, no matter how long it took for them to eat it. She was undeterred by tears, tantrums, or even vomit. When weighed against the possibility of a lifelong feeding tube, we opted for this torturous treatment. She was successful in getting my son past his aversions to other foods.

I still have mixed feelings about our decision. The fear of the lifelong feeding tube was real—we knew personally a child with a feeding tube that was going on five years. Knowing this was a choice my autistic child was making and not a medical necessity, we decided we weren’t going to give him the freedom to make that choice.

However, we weren’t at our last resort. He wasn’t starving—he was still eating two foods. He might have gotten better on his own. The treatment we put him through was considered the last resort before a feeding tube, and I’m not sure we were really there yet.

The treatment was traumatic. Imagine being forced to eat a food you hate. You can’t spit it out. And no matter how unpleasant you find it, you must eat it. I wouldn’t want to go through that. But then again, I wouldn’t want a feeding tube either.

I’m not certain we did the right thing. He eats a wide variety of food now. If anything, he has the more common problem of weight control. He no longer has issues with eating—other than perhaps he likes it too much. Does that end justify the means? If you’re faced with that choice, you’ll need to answer it for yourself and your child. There isn’t a clear choice that’s 100% correct, and anyone who tells you otherwise is selling something or riding the high horse of ignorant righteousness.

ABA Therapy

Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) is a type of therapy that focuses on improving specific behaviors, such as social skills, communication, reading, and academics, as well as adaptive learning skills like fine motor dexterity, hygiene, grooming, domestic capabilities, punctuality, and job competence.

When we learned my son was autistic, the only treatment with any scientific validity was ABA therapy. It was prominently featured in the book “Let Me Hear Your Voice,” which is often one of the first books parents find on the subject. It provides hope—mostly false hope—to many parents, and the book remains popular today.

But it also contributes to the false idea that autism means “broken,” which is why I don’t recommend it to people. It’s helpful for those struggling with despair or those who need denial as a temporary coping mechanism, but I found other resources more valuable for our long-term journey.

ABA was useful for my son. He acquired some life skills that serve him well today. He benefited greatly from the close attention of caring people. But it didn’t really do anything to “cure” his autism because autism isn’t something to be cured. ABA is a coping strategy, not a treatment in the traditional sense. It’s not perfect, but it’s better than all the other options available.

ABA does have limitations. It focuses on rote learning, which many autistic children excel at but which doesn’t always translate to real understanding. Children often struggle to generalize what they learn in therapy to other situations. In some ways, it’s akin to pet training—children learn to respond to specific cues without necessarily understanding why they’re doing it.

Despite these limitations, ABA will likely be a big part of any service program offered by schools or state agencies. There are newer, more child-centered approaches emerging all the time, so if you’re considering this path, I’d encourage you to buy a current book on the subject rather than relying on older resources that may not reflect the latest thinking.

In the end, what helped my son most wasn’t any particular therapy or treatment—it was being surrounded by people who accepted him exactly as he was, who worked with his strengths rather than constantly trying to “fix” his weaknesses. Sometimes the best medicine isn’t medicine at all—it’s love, patience, and the willingness to see your child for who they are, not who you once thought they would be.