The social challenges of raising a child with special needs run deep, far deeper than most people realize until they’re living it themselves. They ripple through every aspect of your life in ways both expected and surprising.

My wife and I are both introverts by nature. We’ve never had a large circle of friends or a particularly vibrant social life, even before our son came along.

Our comfort zone has always been spending time with family and a few close friends who feel like family. This worked well for us—it’s who we are at our core. But when you add a child with special needs to the equation, your already small social circle can shrink even further.

School Days and Segregation

When my son started school, he was placed in segregated classes with other children with special needs. This single decision shaped our social landscape in profound ways. Our school-related social connections became almost exclusively with other parents who had children with special needs. That’s how I met and got to know a number of families walking similar paths.

My wife often lamented that our circle was so limited. We couldn’t just naturally join in with the much larger community of parents who had typical children. We weren’t going to meet those parents through classroom acquaintances because we wouldn’t be attending their birthday parties or cheering from the sidelines at typical sporting events. We were fortunate to live in a large metropolitan area where programs for children with special needs could flourish. The special needs baseball league became a bright spot for us. There, we met many wonderful families who understood our daily reality without explanation.

The Painful Truth About Social Connections

One of the first things that stands out when you’re raising a child with special needs is that many parents of typical children want nothing to do with you. I understand the reasons—special needs children often struggle with socialization, and parents of typical children simply don’t know how to deal with the differences. But understanding doesn’t make it any less painful.

All those parents I thought I would make friends with? It didn’t happen. The playground chats never evolved into coffee dates or family dinners. The invitations never came.

What’s even sadder is that this kind of discrimination happens within the special needs community itself. Parents of children with milder challenges sometimes avoid families with more severely affected children. They worry their children might pick up “bad habits” or behaviors. They desperately want their children to spend time with typical peers where they believe proper socialization happens.

The result? Parents of children with the most severe challenges end up being the most socially isolated of all. This breaks my heart. I feel deep compassion for their situation, but there isn’t much I can do to change it. The social dynamics are as real as they are painful.

The Inclusion Debate

There’s an ongoing debate in special education about inclusion in regular classrooms. One of the main arguments for inclusion is that it allows children with special needs to learn proper socialization skills from their typical peers. The problem? It usually doesn’t work the way people hope it will.

I remember our friends who sued the school system to provide an inclusive classroom experience for their son. The school complied, providing a dedicated aide and full inclusion in a regular classroom. If your family has the resources to lawyer up and fight the schools, you can win some pyrrhic victories. It’s expensive, but in some districts, it might be a necessary step.

The outcome for this child, however, was a disaster. He needed more attention than even a devoted aide could provide. He couldn’t focus on instruction without disrupting the class. He was visibly unhappy with the situation and the rules being imposed on him. And since he was the only one with an aide, he became painfully aware of his differences. After several difficult weeks, our friends asked the school to return him to a special class.

For students with more significant challenges, specialized classes are generally better suited to their needs. Our school system used a hybrid approach—they would place our son in classes with typical children when he could handle it, but provided a more structured environment when he needed it. This middle path is usually better for those who need more support.

Many parents imagine that inclusive learning will somehow “cure” their child. It’s a solution born more from denial than from an objective evaluation of what’s best for the child. They believe their special child will observe typical children and somehow absorb their behavior patterns. They believe their child will be welcomed as part of the social group and become an integral part of classroom activities. In short, they believe inclusive learning will solve all their problems.

Since those outcomes rarely materialize, it shouldn’t be surprising when inclusive settings don’t turn out well for many children with significant needs.

Friendship and Connection

My son has no friends—not in the conventional sense. He maintains no relationships outside our family. He can’t carry on a conversation like a typical adult. On a good day, he might manage a brief three or four-turn exchange with a kind and understanding stranger.

He has no concept of social cues, body language, or the countless subtle ways people communicate with each other. He shows no interest in playing with friends, hanging out, or spending time with peers. He enjoys video games, but mostly the solitary ones where interaction isn’t required.

In many ways, I’ve become my son’s best friend. I end up providing the social experiences he would ordinarily have with others his age. I take him everywhere I go, and he participates in nearly everything I do. I listen to every word he says, even when he’s spouting complete nonsense or repeating scripts from movies or YouTube videos.

This has become one of my spiritual practices, actually. When my son recites a script—something he does frequently—I have choices in how I respond. I could feel bored with the lack of meaningful content. I could feel sad that his mind seems to lack original thoughts. I could travel down those rabbit holes of despair over and over again.

Instead, whenever I hear him speak, I feel thankful. There was a time when we didn’t know if he would ever talk at all. We know other families whose children are completely non-verbal. That perspective helps me find gratitude in the midst of repetition.

My son has no shortage of social interaction with me and his family. He’s surrounded by people who love him deeply. And after we die, he will have caring people in his life. But he will never have long-term friendships, romantic partners, or people in his life who aren’t either family or paid caregivers.

That’s the reality of who he is, and accepting this truth has been part of our journey.

Special Versus High-Functioning

My son is special in ways that are immediately apparent to anyone who meets him. Due to his limited language and social skills, it takes just one interaction for people to recognize his challenges.

When we moved from one county to another within our state, we needed to be interviewed to verify his eligibility for ongoing services. The examiners are trained to look for fraud—people who might exaggerate disabilities to gain government assistance. When the worker interviewed my son at our home and asked about his care in our new place, my son replied in his typical rapid-fire manner:

“Googleplex, googleplex black, white, new earth, Hubble telescope 4.5 billion years old, sun biting earth, red and blue make purple, save it until 2080, yes!”

The enthusiastic “yes!” at the end came with his characteristic gusto. Our services transfer was approved without delay.

Being visibly “special” means people generally give him the benefit of accommodating his limitations. Nobody mistakes him for a typical adult capable of independence. This places lower expectations on him and makes people more likely to forgive him when he fails to conform to social norms. Realistically, this has made both his life and ours much easier.

From what I’ve observed, higher-functioning individuals on the spectrum face greater challenges in many ways. They need to interact in a typical world but lack the full set of skills to do so effectively. They often have stronger desires for family and friendships but face significant difficulties in forming and maintaining relationships. Higher-functioning adults typically qualify for fewer services and supports. Many are expected to hold down jobs, but they often lack the skills to sustain themselves in competitive employment.

They’re more vulnerable to scams and predatory lending. They frequently end up in difficult circumstances—substandard housing, poor healthcare, limited resources—sometimes at the mercy of those who would exploit them. Our capitalist system, designed in part to force capable people to work, ends up subjecting those with invisible special needs to tremendous hardships.

Encounters with the World

Over the years, we’ve had our share of challenging incidents with strangers. When my son was seven, we attended a family reunion. Many out-of-town visitors, including our family, stayed at the same hotel. On Saturday morning, about twenty of us gathered for the continental breakfast. The only other people in the room were two older German tourists.

My son was going from one family member to another, giving hugs. He wasn’t used to being around so many relatives at once and was making the most of it. Having only seen many of these relatives once or twice before, he wasn’t entirely clear on who was family and who wasn’t.

As he made his rounds, he stopped and hugged the arm of one of the German women. She was annoyed, and I apologized, explaining that he didn’t realize she wasn’t family since everyone else in the room was related to us. A few minutes later, he did it again, and she became furious. She launched into a lecture about how we should control our unruly child.

She was right in one sense—we hadn’t stopped him from hugging her arm twice. But was her angry lecture really necessary? Was a child’s hug so offensive that she needed to express near rage? Could she not see that he was different and meant no harm?

Were we leaning too heavily on the “he’s special” defense when we should have been more careful? Perhaps. If we had realized how upset she would become, we certainly would have kept him as far from her as possible. But it was hard for us to imagine that a loving child giving hugs could provoke such anger.

I tried to feel compassion for her, imagining she must not be accustomed to expressions of love and reacted out of discomfort. The incident ruined the day for my wife, who was convinced the woman was just a mean-spirited old battle-ax with no redeeming qualities. I found it difficult to convince her otherwise. If I’m honest, at the time, I probably agreed with my wife, so any counsel would have been half-hearted.

Letting Go of Independence

There was another incident that marked the end of my illusions about my son’s potential independence. I used to allow him to go on a specific theme park ride by himself. He could wait in line, hold his place, and follow basic staff instructions. A well-supervised theme park seemed like a safe place to give him a taste of freedom.

Unfortunately, something happened while he was in line. Since I wasn’t there to witness it and since his answers to questions aren’t reliable, he couldn’t defend himself against whatever accusations arose. That’s when the harsh reality hit me—he could never be left alone and unsupervised. He was simply too vulnerable.

I denied this truth to myself for a long time. I wanted desperately to believe he could have some measure of independence. I think every parent wants to believe their child will grow into an autonomous adult. My attachment to this hope fed my denial, and my denial caused me to make a poor decision that put my son in circumstances he couldn’t handle on his own. It was a painful lesson.

Reaching Out His Way

Despite his limited success, my son still yearns to connect with people, even if only for a brief moment. When we’re out in public, he often says hello to random strangers while vigorously waving his hands. His hello/goodbye wave isn’t as polished as the British queen’s, but what he lacks in technique, he makes up for in enthusiasm.

I try to guide him to wait until someone is making eye contact and smiling—he certainly gets more positive responses when he does that. But he still often blurts out “hi” to people who aren’t paying attention to him, catching them completely off guard. Although he’s an introvert like his parents, his exuberant side emerges when he’s in a particularly good mood and we’re out in public.

Accept Us or Go Away

If you’re more extroverted than we are, this chapter might have been especially difficult for you to read. There are undeniable social limitations when you have a child with special needs. We follow a simple rule that has saved us time and effort on false friendships: we socialize as a family most of the time.

If my son isn’t welcome at a family event, we don’t want to be there either. My wife and I refuse to attend gatherings with other children without bringing our own. And because we mostly connected with parents who also had children with special needs, this approach generally worked well for us.

In those instances where we declined invitations, I never felt remorse or wondered if we’d missed making lifelong friends. How could I possibly sustain a friendship with someone who couldn’t accept my son? While this practice may have limited our social circle, I believe it limited it for the better.

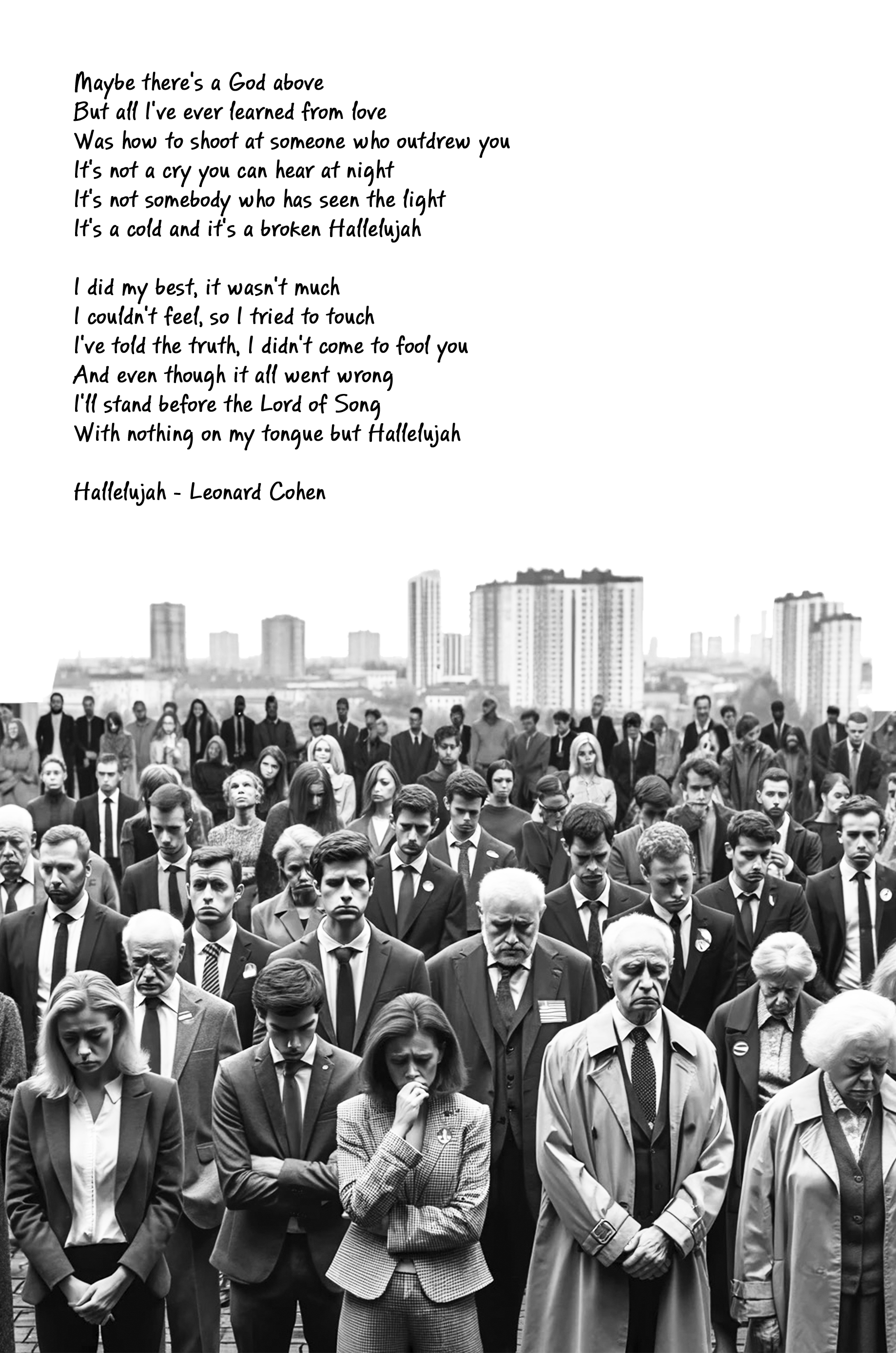

Our approach might seem isolating to some, but for us, it created a boundary of respect—both for our son and for ourselves. Accept us as we are, or we’ll go our separate ways. There’s a quiet dignity in that choice, a broken hallelujah that honors the reality of our lives without apology.